Australian scientists have confirmed the discovery of a new species of funnel web spider that’s nearly twice the size of its already fearsome relatives. The Newcastle funnel web spider, scientifically named Atrax christenseni, has been found in a 25-kilometer radius around Newcastle, New South Wales.

The spider, nicknamed “Big Boy,” measures up to 9.2 centimeters in leg span, dwarfing the typical 2.5-centimeter body length of regular male funnel webs. “They barely fit in the park’s holding jars. People mistook them for huntsmans. When one prowled across a benchtop, you could hear its footsteps,” says Kane Christensen, the spider expert at Australian Reptile Park who first noticed these unusually large specimens.

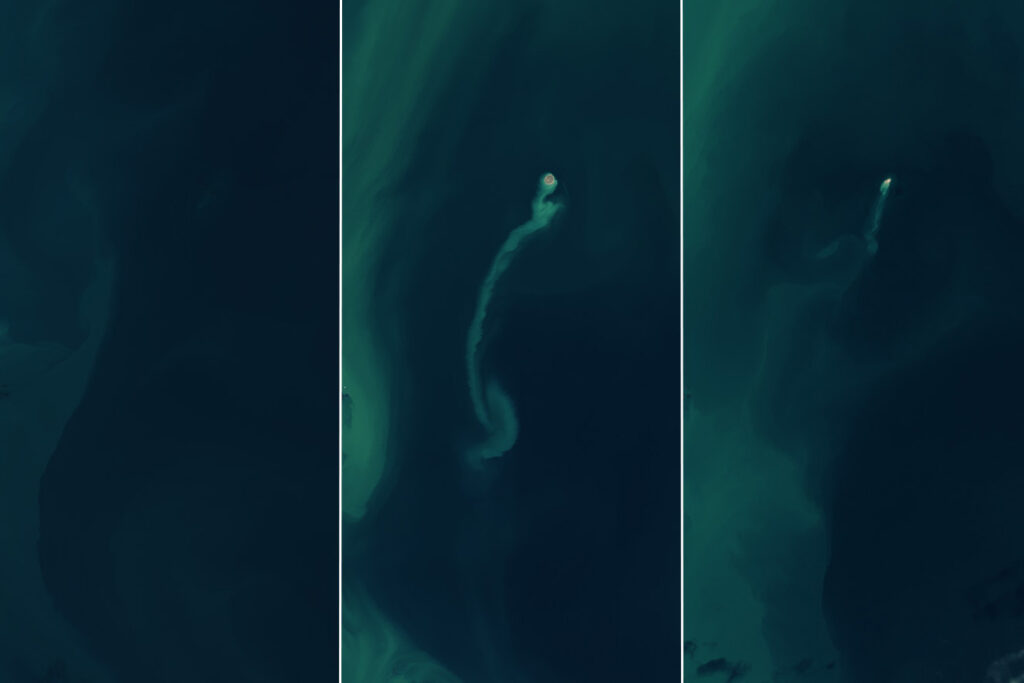

The discovery emerged from a systematic pattern of oversized funnel webs being brought to the Australian Reptile Park’s venom-milking program. The park’s collection included record-breakers like Colossus in 2018, Megaspider in 2021, and most recently, Hemsworth – named after Australia’s famous acting family – which set a new size record at 9.2 centimeters.

Dr. Helen Smith, an arachnologist at the Australian Museum, explains that the research has split what was previously known as the Sydney funnel web into three distinct species. “The ‘real’ Sydney funnel web, Atrax robustus, calls the north shore and Central Coast home. That’s the heartland,” says Smith. The southern Sydney funnel web, now classified as Atrax montanus, has a wider distribution extending into the Blue Mountains.

Professor Geoff Isbister, a clinical toxicologist at the University of Newcastle, points out potential increased risks with the new species. “The biggest spiders are more likely to inject enough venom to cause envenoming. I suspect what they’re calling the ‘Big Boy’ is more likely to be dangerous.” However, he emphasizes that current antivenom remains effective against all funnel web species.

Similar Posts

The discovery has conservation implications too. The exact locations of these Newcastle funnel webs remain undisclosed to protect them from collectors. “As soon as collectors get a whiff of a new species, there’s a huge trade in invertebrate specimens in Australia,” Smith warns. “They could make quite a dent in the population.”

The species’ scientific name honors Kane Christensen, who joined the Australian Reptile Park in 2003 as a volunteer venom milker. His keen observation of unusually large specimens led to this significant discovery. “That was, after my kids being born, one of my proudest days,” Christensen shares about learning the species would bear his name.

Photo Source: Australian Museum

For public safety, the Australian Reptile Park continues its vital role in collecting funnel webs for antivenom production. Emma Teni, a handler at the park, advises that encounters typically occur between November and April during breeding season. “These guys are normally hiding in their burrows – but they might accidentally walk into a garage or somewhere in the home,” she explains.

While no deaths have occurred from funnel web spider bites since antivenom became available in 1981, the discovery emphasizes the importance of continued research and vigilance. The venom induces muscle spasms, profuse sweating, tears, and a rapid pulse, as documented in recent cases including an 11-month-old “miracle baby” who survived a bite in early December.

Photo Source: Australian Museum

The evolution of these distinct species occurred during cycles of wet and dry climates, with spiders becoming isolated in moist gullies during dry periods. This isolation led to the development of separate species, adding another fascinating chapter to Australia’s rich biodiversity story.