Over 78 species of Australian birds have developed smaller bodies and larger beaks in response to rising temperatures, research from Deakin University reveals. These physical changes have been documented through data from museum specimens and long-term shorebird monitoring by the Victorian Wader Study Group and the Australasian Wader Studies Group.

“Modelling shows that fractions of a degree in warming can make an enormous difference to many species,” states Dr. Carla Archibald, Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellow. “More habitat means a better chance to persist, especially as species will also face additional threats such as land use change, invasive species, and other challenges.”

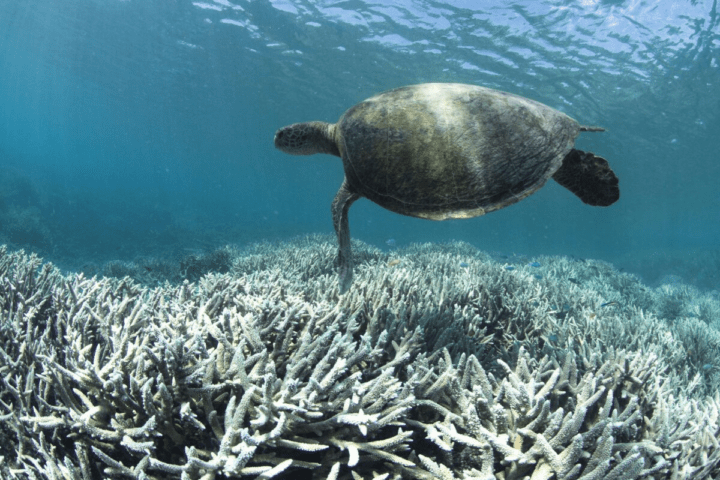

This research conducted by Deakin University in collaboration with the World Wide Fund for Nature-Australia (WWF-Australia) shows that limiting global warming to 1.5°C rather than letting it hit 2°C would retain more suitable habitat for threatened species.

Temperature Effects on Bird Physiology

Bird beaks contain blood vessels that transfer heat from the body’s core to the beak surface, where it is lost to the environment. In short-term periods of high temperature, both body and beak size can decrease, possibly due to reduced food availability and stunted growth.

During short-term periods of extreme temperatures, having a big beak can be a liability, as hot air from the environment will move into the beak, causing the bird to heat up too much, with potentially fatal consequences.

The purple-crowned fairy-wren faces severe threats from climate change. This bird, weighing between 9 and 13 grams, is lighter than a 50-cent piece. Scientific models predict that a 2°C global temperature increase would eliminate 62% of their river-fringing vegetation habitat in northern Australia.

More Stories

Data Collection Methods

The research utilized two primary data sources:

- Community scientist observations from Victorian Wader Study Group and Australasian Wader Studies Group, spanning nearly 50 years and including measurements of bill length, wing length and body mass in more than 100,000 individual birds

- 3D scans of over 5000 museum specimens, measuring beak surface area and wing length across multiple species

Future Outlook

While some species demonstrate physical changes in response to warming temperatures, others show no such adaptations. This variation raises questions about whether non-adapting species don’t need to change or cannot adapt to changing conditions.

These findings emerge as Australia prepares its 2035 nationally determined contribution to the Paris Agreement, due in February 2025. Current climate science indicates that Australia would need to cease approvals of new fossil fuels and wind down existing infrastructure earlier than planned to maintain a positive trajectory.