A groundbreaking discovery shows how the endless battle between predators and prey began 517 million years ago. This finding helps explain why animals today, from house cats to humans, have natural defenses against threats.

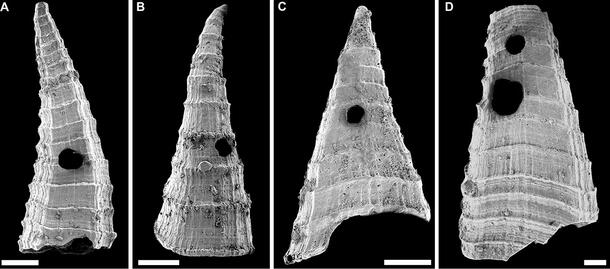

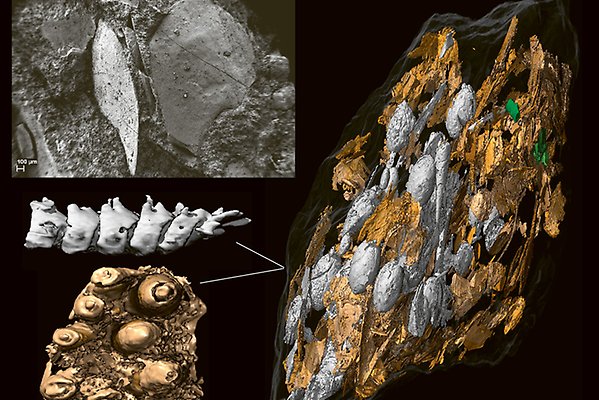

Scientists found tiny ancient shells in South Australia with holes made by predators. These shells, some no bigger than a grain of sand, tell an amazing survival story that continues in nature today.

Think of how your cat’s sharp claws help it catch mice, while mice have become faster and more alert to escape. This same back-and-forth happened with ancient sea creatures. When predators got better at breaking through shells, their prey developed thicker armor to survive.

“Predator-prey interactions are often touted as a major driver of the Cambrian explosion, especially with regard to the rapid increase in diversity and abundance of biomineralizing organisms at this time,” says Russell Bicknell from the American Museum of Natural History, who led the research. His team studied over 200 fossil shells using powerful microscopes to uncover this ancient pattern.

The research explains why modern animals have features like tough shells, sharp teeth, or the ability to run fast. Even humans benefited from this evolutionary race – our ancestors developed better eyesight and bigger brains to spot and outsmart predators.

Today, we see similar patterns everywhere. Mosquitoes develop resistance to bug spray, forcing scientists to create new formulas. Bacteria evolve to fight antibiotics, pushing medical researchers to develop new medicines. Understanding these patterns helps doctors and scientists protect public health.

The scientists studied a tiny sea animal that lived long ago. When predators tried to eat it by making holes in its shell, it grew stronger shells to stay safe. It’s similar to examples we see in nature today, like snakes developing stronger venom while their prey builds resistance.

Similar Posts

“This critically important evolutionary record demonstrates, for the first time, that predation played a pivotal role in the proliferation of early animal ecosystems and shows the rapid speed at which such phenotypic modifications arose during the Cambrian explosion event,” says Bicknell. His team found clear evidence that the shells got stronger each time predators found new ways to break them.

This discovery matters for our lives today. Think about how bacteria evolve to fight antibiotics, pushing scientists to develop new solutions. Nature taught animals to adapt, and we see this pattern continuing.

These ancient shells tell us something important: getting better at protecting ourselves is a natural part of life. When we face new challenges – like evolving bacteria or the need for better medicines – we can learn from nature’s example to find solutions.