A 500,000-year fossil study of the Southern Ocean’s deep-sea ecosystem reveals critical insights into climate change impacts and potential risks of marine carbon removal technologies. The research, published in Current Biology, shows how temperature variations and food availability have shaped deep-sea communities over millennia.

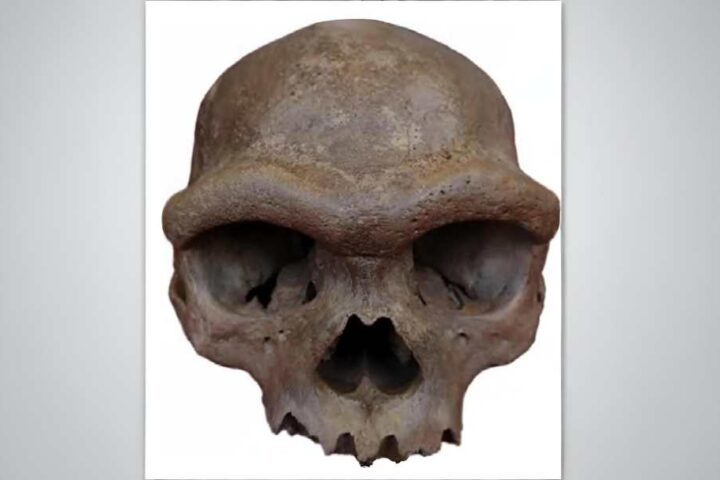

Led by Professor Moriaki Yasuhara and Ms. Raine Chong from the University of Hong Kong’s School of Biological Sciences, alongside Dr. May Huang from Princeton University, the study analyzed deep-sea fossil records extracted from sediment cores. Their findings expose the delicate balance of deep-sea ecosystems and raise concerns about proposed climate intervention strategies.

The research demonstrates that deep-sea organisms show sensitivity to temperature fluctuations. These creatures, adapted to extreme conditions, rely entirely on descending organic material—known as marine snow—for sustenance, as the sunlight can’t penetrate at that depth, therefore preventing local food production.

“Deep sea covers over 40% of our planet’s surface, and its ecosystem is known to be highly vulnerable,” states Professor Yasuhara. “The vast majority of species remain unknown to us.” He emphasizes the necessity for careful ecosystem impact assessments.

Researchers employed ocean-based climate intervention (OBCI) technologies, particularly marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR). These methods are technologically advanced and nearly ready for implementation, though their ecological impact remains uncertain. They operate on principles of iron fertilization, which aims to enhance carbon sequestration by stimulating surface productivity and could significantly alter deep-sea communities.

More Stories

As per the study, the current Southern Ocean deep-sea ecosystem structure established itself 430,000 years ago. This finding provides crucial context for understanding potential human-induced changes to this long-standing system.

Professor Yasuhara notes that the Southern Ocean functions as an early warning system for global climate change, given its crucial role in ocean circulation patterns. “I hope such a long-standing ecosystem won’t be completely altered in the near future,” he states, expressing concern about escalating human-induced warming effects on global climate systems.

The study’s implications extend beyond academic interest, offering vital insights for policymakers considering climate intervention strategies. As pressure mounts to address climate change, this research underscores the importance of protecting deep-sea ecosystems while pursuing carbon reduction solutions.