A groundbreaking study from the University of Edinburgh has uncovered that around 404,000 people in England are living with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). This figure represents a 62% increase from the previously accepted estimate of 250,000 cases.

Researchers analyzed NHS data from over 62 million people to reveal not just higher numbers, but troubling gaps in who gets diagnosed based on ethnicity and location.

The Hidden Scale of ME/CFS

The study, published in the medical journal BMC Public Health, shows that nearly 1% of women (0.92%) and 0.25% of men in England are affected by this debilitating condition. Previous estimates relied on UK Biobank data, which researchers say included too many healthier individuals, leading to an undercount.

Professor Chris Ponting, who led the study at the MRC Human Genetics Unit, explained: “The NHS data shows that getting a diagnosis of ME/CFS in England is a lottery, depending on where you live and your ethnicity. There are nearly 200 GP practices – mostly in deprived areas of the country – that have no recorded ME/CFS patients at all.”

A “Diagnosis Lottery” Based on Ethnicity and Location

The research revealed stark differences in diagnosis rates. White people in England are almost five times more likely to receive an ME/CFS diagnosis than those from other ethnic backgrounds. People from Chinese, Asian/Asian British, and Black/Black British backgrounds face diagnosis rates 65% to 90% lower than white British individuals.

This pattern held true across different regions and for both men and women.

Location also plays a major role in determining who gets diagnosed. Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly showed the highest rates, while North West and North East London reported the lowest. Of 6,113 large English GP practices, 176 – primarily in deprived areas – had no recorded ME/CFS patients at all.

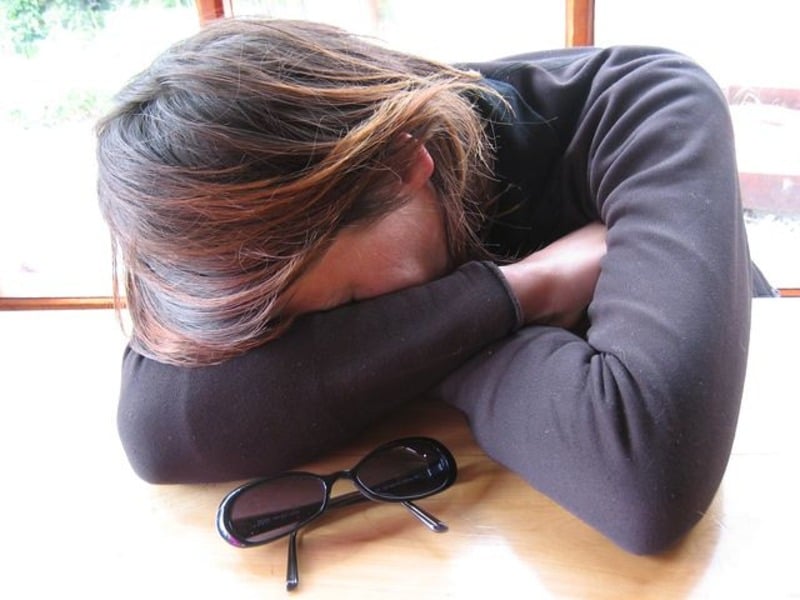

Women and Age Patterns

The study found that women are six times more likely than men to have ME/CFS during middle age. The condition peaked around the age of 50 for women and a decade later for men, with women six times more likely to have it than men in middle age.

Similar Posts

What Is ME/CFS?

ME/CFS is characterized by extreme fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest. A key feature is post-exertional malaise – a delayed, dramatic worsening of symptoms following even minor physical effort. Patients also experience pain, cognitive problems (“brain fog”), and severe energy limitations.

Despite its serious impact, the condition has no specific diagnostic test or known cure, and its causes remain unclear.

The Importance of Diagnosis

Gemma Samms, an ME Research UK-funded PhD student involved in the study, emphasized why proper diagnosis matters: “People struggle to get diagnosed with ME/CFS. Diagnosis is important because it validates their symptoms and enables them to receive recognition and support.”

The findings confirm what many patients have reported – feeling “invisible and ignored” by the healthcare system.

Calls for Action

The researchers say their results should lead to improved training of medical professionals and increased research into developing accurate diagnostic tests.

Dr. Charles Shepherd, medical advisor at the ME Association, noted: “Over the past year, the ME Association has been discussing with charity colleagues and other organizations how the current estimate of around 250,000 people with ME/CFS is almost certainly an underestimate given the growth in population since this figure was first used and the large number of people who now have post-Covid ME/CFS.”

Future Developments

The ME Association has invested in a Canadian clinical trial of low-dose naltrexone as a potential treatment for both ME/CFS and Long Covid, with results expected in early 2026.

Additionally, the Department of Health and Social Care is expected to publish an ME/CFS Delivery Plan aimed at improving attitudes, education, and research in the field.

This landmark study, funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research, the Medical Research Council, and the charity ME Research UK, marks an important step in understanding the true burden of ME/CFS in England and highlights the urgent need to address healthcare inequalities affecting its diagnosis and treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions

ME/CFS (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) is a long-term condition characterized by extreme fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest. The key feature is post-exertional malaise – where even minor physical or mental effort can cause symptoms to dramatically worsen for days or weeks. People with ME/CFS also experience pain, cognitive problems (“brain fog”), and severe energy limitations that can significantly impact their ability to work, socialize, and perform daily activities. Currently, there is no specific diagnostic test or known cure for the condition.

According to the new University of Edinburgh research, approximately 404,000 people in England are living with ME/CFS. This is a 62% increase from the previously accepted estimate of 250,000 cases. The study found that nearly 1% of women (0.92%) and 0.25% of men in England are affected by the condition, making it much more common than previously thought.

Previous estimates of ME/CFS prevalence in England (around 250,000 cases) were based on data from the UK Biobank population. The researchers found that this data source contained disproportionately more people who were in better health, leading to an undercount of ME/CFS cases. The new study analyzed NHS data from over 62 million people in England, providing a much more comprehensive and accurate picture of how many people are affected by the condition.

The research revealed significant disparities in who gets diagnosed with ME/CFS. Women are six times more likely than men to have ME/CFS during middle age, with the condition peaking around age 50 for women and about a decade later for men. White people in England are almost five times more likely to receive an ME/CFS diagnosis than those from other ethnic backgrounds. People from Chinese, Asian/Asian British, and Black/Black British backgrounds face diagnosis rates 65% to 90% lower than white British individuals. Location also plays a role, with Cornwall showing the highest diagnosis rates while parts of London show the lowest.

The “diagnosis lottery” refers to the study’s finding that receiving an ME/CFS diagnosis in England depends heavily on factors like where you live and your ethnicity, rather than just your symptoms. The researchers found that of 6,113 large English GP practices, 176 – primarily in deprived areas – had no recorded ME/CFS patients at all. This suggests a systematic inequality in who gets diagnosed, with Professor Chris Ponting noting: “The NHS data shows that getting a diagnosis of ME/CFS in England is a lottery, depending on where you live and your ethnicity.”

Following these findings, researchers and medical advisors are calling for improved training of medical professionals to better recognize and diagnose ME/CFS, as well as increased research into developing accurate diagnostic tests. The ME Association has invested in a Canadian clinical trial of low-dose naltrexone as a potential treatment for both ME/CFS and Long Covid. Additionally, the Department of Health and Social Care is expected to publish an ME/CFS Delivery Plan aimed at improving attitudes, education, and research in the field to address the healthcare inequalities affecting diagnosis and treatment.