A decade-long study by Karolinska Institutet, published in The Lancet Planetary Health, has revealed startling new data about air pollution’s impact on public health in India. The research analyzed air quality data from 655 districts across India, tracking the relationship between fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and mortality rates from 2009 to 2019.

The numbers tell a sobering story: for every 10 microgram per cubic metre increase in PM2.5 concentration, mortality rates rose by 8.6%. “We found that every 10 microgram per cubic metre increase in PM2.5 concentration led to an 8.6 percent increase in mortality,” says Petter Ljungman, researcher at the Institute of Environmental Medicine at Karolinska Institutet.

These microscopic particles, measuring less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, penetrate deep into our lungs and bloodstream. The research team discovered that approximately 3.8 million deaths during the study period were linked to PM2.5 levels exceeding India’s current air quality standard of 40 micrograms per cubic meter. When measured against the World Health Organization’s stricter guideline of 5 micrograms per cubic meter, the death toll rises to 16.6 million – nearly 25% of all mortality during these years.

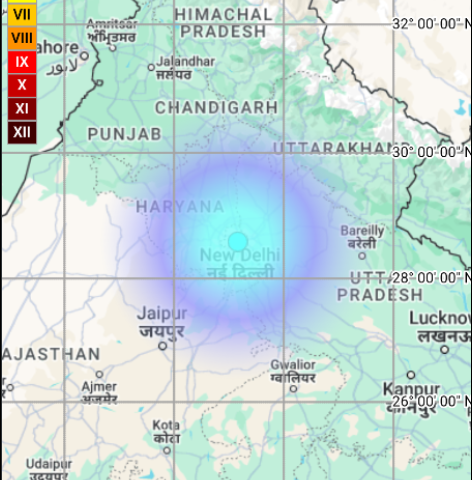

“The results show that current guidelines in India are not sufficient to protect health. Stricter regulations and measures to reduce emissions are of utmost importance,” Ljungman explains. His concern is well-founded – the entire population of India, roughly 1.4 billion people, lives in areas where PM2.5 levels exceed WHO guidelines. Some regions recorded levels as high as 119 micrograms per cubic meter.

More Stories

The Centre for Science and Environment’s recent data from Delhi reinforces these findings. In 2024, Delhi’s annual PM2.5 concentration reached 104.7 µg/m³, more than double India’s national standard. Winter pollution peaks hit 732 µg/m³, marking a 26% increase from the previous year. “This cannot be seen as an annual aberration due to meteorological factors and the consistent rise indicates the impact of growing pollution in the region,” says Anumita Roychowdhury, executive director of research and advocacy at CSE.

Despite India’s national air pollution control program operating since 2017, PM2.5 levels continue rising in many areas. The research team found that these particles can travel hundreds of kilometers, requiring both local emission reductions and broader regional strategies. “Our study provides evidence that can be used to create better air quality policies, both in India and globally,” Ljungman notes.

The study’s methodology sets it apart from previous research. By analyzing actual mortality data rather than estimates, it provides unprecedented insight into air pollution’s health impact. The findings suggest that earlier studies may have underestimated the scale of India’s air quality crisis, with implications for public health policy worldwide.